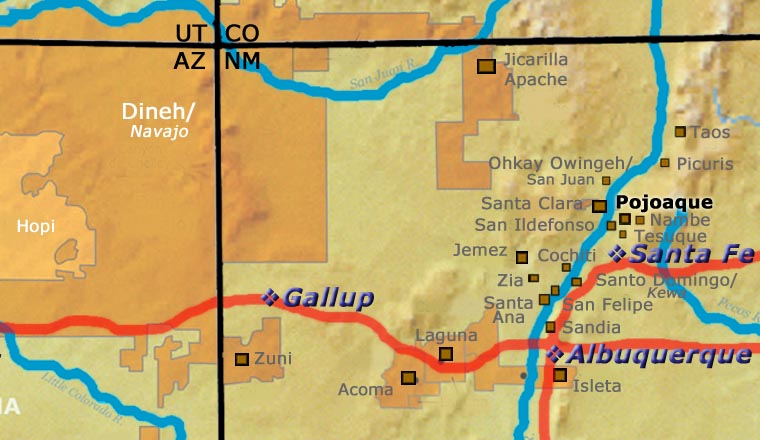

Pojoaque Pueblo

Poeh Culture Center at Pojoaque

The Pojoaque Pueblo area was first settled around 500 AD and the population grew until it peaked in the 1500's. That was about the same time the Spanish first arrived. The first Franciscan mission was built at the pueblo in the early 1600's but the people were already hurting under the impact of Spanish taxes, forced labor and continuous efforts to force conversion to Christianity. That all added up to Pojoaque being in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Immediately following the revolt, Pojoaque was abandoned and wasn't resettled until about 1706 when many Pojoaque's trickled back from the Cuartelejo area on the plains of west Kansas. By then the major Spanish retributions had died down and it was relatively safe to return, surrender and pledge allegiance anew. Franciscans were also being replaced with Jesuits and the religious fervor receded from the heights reached during the Inquisition.

The population of the reestablished pueblo grew slowly but they saw increasing problems from non-Indian encroachment until President Abraham Lincoln recognized the pueblo as an official tribe. Some documents say he awarded the tribe with an official land grant in 1864 and gave a silver cane to the tribe's governor. Other documents say the tribe was given a quit-claim deed... However it worked out, the tribe did gain some legal standing and was able to reestablish its presence until 1900 when a severe smallpox epidemic caused the pueblo to be abandoned again (the Cacique (the tribe's religious leader) died and Governor Jose Antonio Tapia left the reservation to find work).

In 1934 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs placed newspaper ads around the area calling for all Pojoaque tribal members to come back and reoccupy the pueblo lands or tribal ownership would be dissolved under the Indian Re-Organization Act. Shortly, 14 members of the Villareal, Tapia, Romero and Gutierrez/Montoya families were awarded land grants from the Pueblo land base. By 1936 tribal enrollment reached 263 members and Pojoaque became a Federally recognized Indian Reservation.

During the time of abandonment, many Pojoaque tribe members moved to nearby Santa Clara and San Juan Pueblos. Those Pojoaque who were making pottery at the time learned new things from their neighbors and when they later returned to Pojoaque, traditional pottery making changed with all the cross-pollination of styles and designs. Some potters, though, returned to making only traditional Pojoaque styles and designs. Today there is hardly any pottery being made at Pojoaque as so many tribal members are employed in one or another of the tribe's many commercial enterprises.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Pojoaque

$ 250

cata4b054

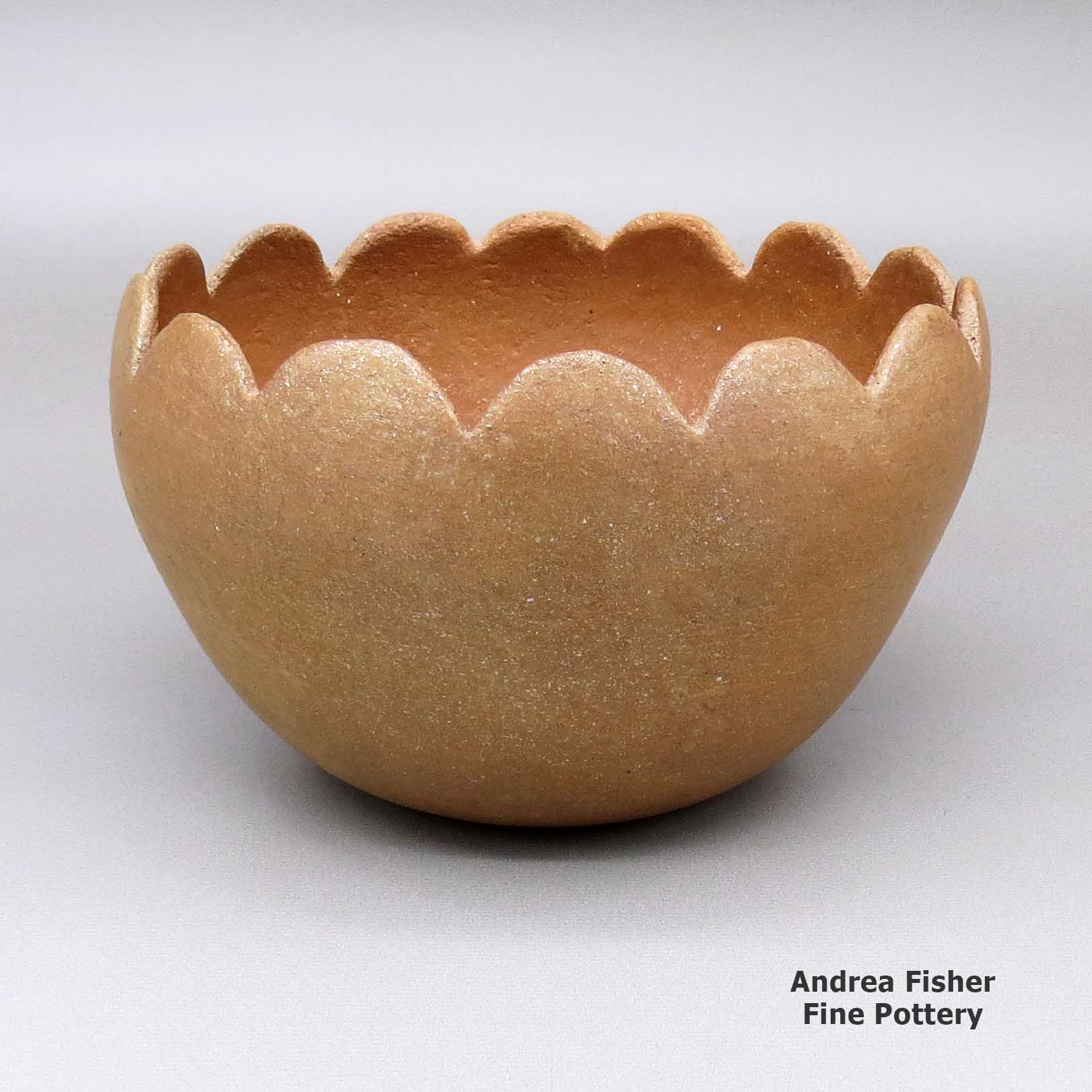

Micaceous gold bowl with a scalloped rim

6.75 in L by 6.75 in W by 4.5 in H

Condition: Very good, pitting and normal wear

Signature: Cordi Gomez Pojoaque Pueblo

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Micaceous Clay Pottery

Angie Yazzie

Taos

Christine McHorse

Navajo

Clarence Cruz

San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

As we understand it, potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have said there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker, heavier and rougher on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and conducts heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner and have a smoother surface. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area of Taos turns golden when fired, it can also be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and San Juan use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home in the Jemez Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Navajo potter who married into Taos Pueblo, uses various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asks of her in the flow of her creating.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. There are some who have learned to successfully paint on a micaceous surface. The undecorated sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of simple shapes is a real testament to the artistry of the micaceous potter.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved